Can aging population trends tame inflation?

By Larry Berman

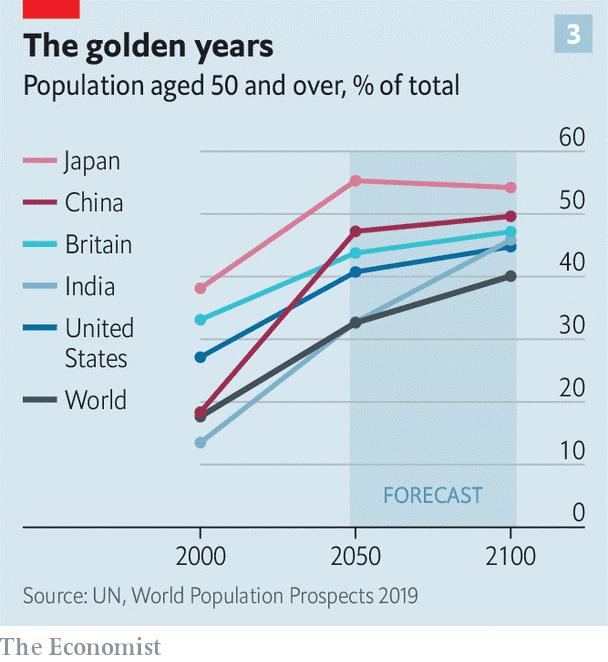

The Economist, one of my favourite weekly reads (or listens these days with audio features), highlights a recent paper examining the effects of demographic change on saving, Etienne Gagnon, Benjamin Johannsen and David López-Salido of the Federal Reserve Board suggest that aging in America may account for about one percentage point of the drop in interest rates since the 1980s. Other research has suggested it could be as much as three per cent. One thing is fact, the world is aging rapidly. Birth rates continue to decline and that will have implications for labour, savings, the cost of money (interest rates), and inflation. The share of global population over the age of 50 rose from 15 per cent in the 1950s to 25 per cent today. It is expected to rise to 40 per cent by 2100 (see chart). Unless young people decide to have larger families on average, the demographic picture will continue to grey. Most expect this to have a mitigating impact on inflation, but some disagree.

We have discussed the impact of demographics for years on Berman’s Call. The demographic impact on your investments can be material. Afterall, aggregate demand, the core driver of GDP, is all about how many people there are, how many are working, how productive they are, and ultimately what they consume. The latest COVID impacts are the affects on the labour market and inflation pressures. If recent fertility trends are anything to go by, India’s birth rate declined to just two children per woman in 2021—below the rate at which births and deaths are in rough balance. India is one of the bullish demographic stories with an average population that is in prime childbearing years (28). Recent history has shown to no surprise, that a growing number of emerging markets have flipped to the slow population growth common in rich countries. Recent research by Matthew Delventhal of Claremont McKenna College, Jesús Fernández-Villaverde of the University of Pennsylvania and Nezih Guner of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona concludes that such transitions—the switch from high mortality and fertility rates to low ones which accompanies economic development—are happening faster over time. The transition took a half century or more 100 years ago, but now tends to be compressed into just two or three decades. Some 80 countries have completed this transition, and in virtually all the rest it is under way. Lower population growth, in theory, should provide slower demand growth. Labour supply shortages driving costs should balance out with more people coming back to the labour force. At least that is the expectation.

Read more @BNN Bloomberg

295 views