How will aging nations pay for their retirees?

If governments rack up debt to support their senior citizens, inflation may be here to stay

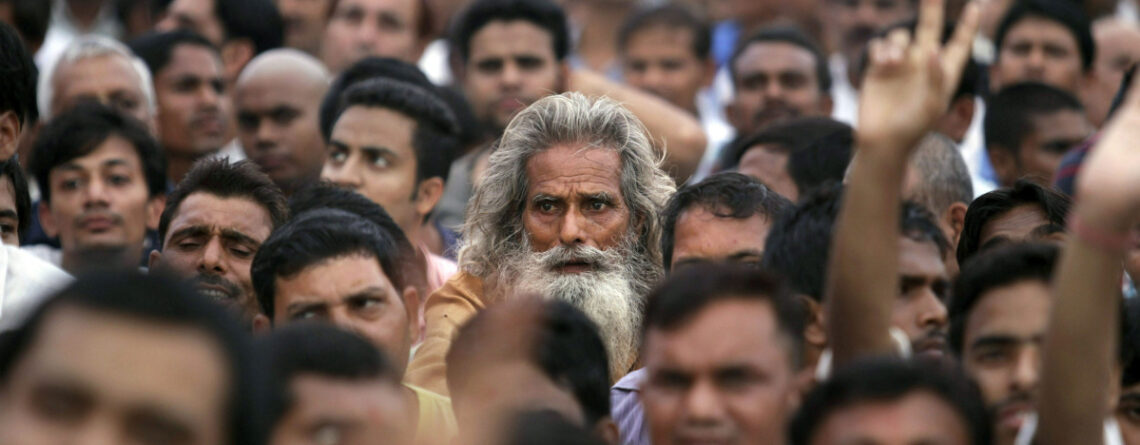

As the world’s population crosses 8 billion, it’s getting older. On average, the bloom of youth came around 1970, when the median age of the world was roughly 21; by 2100, that figure will have climbed to 41 or 42.

Forty is, of course, the new 20—but this number is just an average. Many countries, particularly in Africa, will be younger, but the world’s most prosperous nations and its biggest economies will be considerably older. Their populations of retirees and senior citizens will swell, but their workforces—and, as a result, their tax revenues—will contract. And that presents an economic problem. How will these governments pay pensions, welfare, and healthcare costs for the old, even as they have fewer younger people to tax?

Funding for everything in an older society

Inevitably, governments in the US, Europe, China, and other aging nations will have to take on more debt, so that they can pay for their older citizens. “There was an increase in debt during the pandemic, which worried so many people, but compared to what’s coming, that will be a drop in the ocean,” said Manoj Pradhan, who founded Talking Head Macroeconomics, a research firm in London.

The US public holds almost 100% of GDP in federal debt, which last spiked to that level during World War II. Forecasts by the US Congressional Budget Office indicate a rise in debt to around 180% of GDP by 2050. To support that level of debt, Pradhan said, societies will have to accommodate higher levels of inflation. Things will just cost more in the future.

In combination, economic growth will falter, since working-age populations will shrink. In the US, real potential GDP growth is projected to drop from 2.4% currently to 1.5% in 2043. Some of this can be offset. “If inflation starts eating into savings, people will want to come back to work,” Pradhan said—something that’s happening even now in the US.

Any official move to raise the retirement age will not go down well with people who have been used to thinking of stopping work at 60 or thereabouts, Pradhan said. “Even in Russia, at a time when Vladimir Putin had a lot of popularity, he found it hard to push the retirement age up,” he said. But even if, de facto, people retire later, Pradhan is unsure of “how much this can be juiced. Already, by reducing pension benefits, we’ve made people aware of this.” In the EU, for instance, the labor force participation rate for people between the ages of 55-64 rose from around 43% in 2005 to around 64% in 2019. “I’m not sure how much higher we can drag that,” Pradhan said.

A more durable fix would be to make it easier for women to work. In the US, the labor force participation rate of women is a full 12 percentage points behind that of men. If governments grow smarter about facilitating child care, maternity benefits, and other forms of support for women, they could bring a flood of new workers into the tax net—a boost for gender parity and labor rights, as well as a solution to the demographic drag, all at the same time.

Read More @QZ

265 views